Love You Me

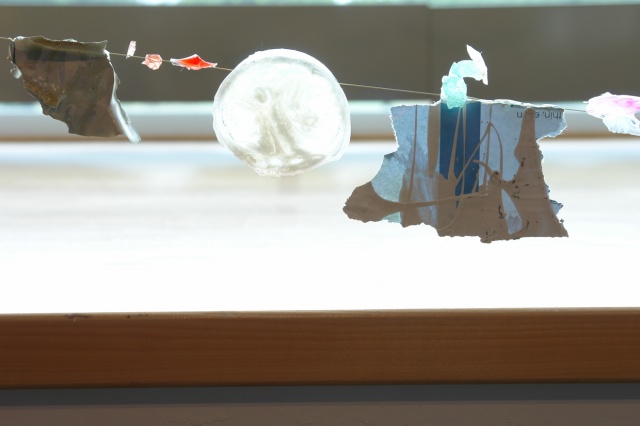

"Danielle Riede’s Love You Me spans the gallery’s windows. While it may be the first thing seen (certainly from outside) it is appropriate to consider it here last, because a portion of Riede’s found materials once belonged to other artists (desiderata, including blobs of paint shed from others’ canvases). The result is not a quote of someone else’s style, rather a physical appropriation of their materials. Riede’s process combines the collecting spirit of Kurt Schwitters with the arranging action of Judy Pfaff. Resin pieces cast from collected objects transform and multiply the readymades. Riede’s adopted orphans traverse delicate tightropes across the windows; the light transforms their appearance by heightening their colors and textures. Viewers will find conversations among the strands, as the abstract forms suddenly take on the appearance of animals or recognizable objects. Riede’s materials are relics connected to specific locations and memories of time; when activated during installation in the gallery, the concerns become more formal than narrative."

- Elizabeth Mix

Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art

Butler University

Complete catalogue essay for "Material Presence" Show

The works of Material Presence have been arranged to facilitate a complex visual dialogue about the nature of materials and processes in contemporary art—some fifty years since Robert Rauschenberg first combined painting and sculpture and sixty since Jackson Pollock made the act of artistic process part of the finished work’s content.

Today the choice of materials remains one of the most basic (but also fundamentally important) decisions an artist makes in the creation of a work. Artists either embrace the inherent qualities of a material, or test its limits. At the same time, a choice of materials implies a dialogue with the history of its use by previous artists.

The left side of the gallery initiates a discussion of the relationship of paint to canvas. Historically paint has been applied to canvas; the artist would either make the paint represent visual reality by (ironically) making the paint strokes invisible to the viewer or, alternately, would embrace the nature of pigment by using brushstrokes as textural elements. Eric Sall’s large canvases Bloody Ridge and Stockpile at first seem to reinforce the viewer’s expectations for painting, but close inspection reveals a combination of classical and expressionistic line—two conditions that typically contradict each other and therefore are not usually found in a single work. Sall’s work is influenced by popular culture and the paintings of Philip Guston but resembles neither. The history of both figural and non-objective painting is suggested but not illustrated. Attempts to classify the style of the work are thus thwarted—it is neither Abstract Expressionism nor Pop Art, rather both and neither simultaneously.

The celebration of paint as an element separate from canvas occurs in Joseph McSpadden’s work. Here it is the canvas that is minimal (rather than the appearance of the brushstrokes); the conceptual issue of what painting “is” is addressed with expressionism rather than cool intellectualism. The artistic mark is pushed to a sculptural extreme reminiscent of Giacometti’s late bronzes; brushstrokes liberated by Monet, exaggerated by Van Gogh and thrown by Jackson Pollock now exists in space independent of the confines of canvas. In McSpadden’s paintings Lucio Fontana’s sliced canvases and Barnett Newman’s illusionistic zips are re-imagined—a dense network of paint sprouts from small strips of canvas suggested organic growth, DNA strands, even evisceration. The specific personalities of the works inspired McSpadden to assign the titles Brooder and Olafur through a process similar to choosing names for children.

On the right side of the gallery a different conversation on the nature of painting takes place. Here, in the work of Wendy White and Scott Grow, the dialogue is less about the liberation of paint than the nature of the support. Wendy White’s Sports Moment embraces space between a traditional stretched painting and a canvas-capped pedestal. A found-object assemblage à la Marcel Duchamp completes this piece which extends Robert Rauschenberg’s investigation into the relationship between painting and sculpture. The fluorescent spray paint conveys a sense of spontaneity and optimism—the energy of athletic motion, the physical exertion that is never captured in a trophy and exists whether or not the athlete ultimately succeeds. The viewer activates the space between the primary elements of the piece, becoming both artist and athlete while completing the work physically and intellectually. Careful viewers will see the repeating of patterns from the pedestal to the stretched canvas, creating a tentative unity. But much of the canvas is left raw; it therefore exerts a presence independent of the paint applied to it.

Scott Grow’s paintings are more about the act of seeing than physical movement through space. Much like anamorphic paintings of the Renaissance, these works need to be viewed from oblique angles. Patient viewers will not find an optically hidden symbolic object, however, rather evidence of the history of the piece and Grow’s artistic process. The glowing surface initially conceals alternating layers of resin and abstract expressionist marks. Unlike Jean Dubuffet, who used glue against paint to create accidents, Grow’s resin and paint layers are carefully calculated. The heavy organic shapes become aesthetic objects rather than painting’s traditional window of illusion. Unlike the shaped canvases of Elizabeth Murray (which communicated narrative content), Grow’s Untitled suggests the history of fresco and mural painting on a conceptual level. Aviator communicates pure form in a way reminiscent of Brancusi’s Bird in Space; the physical light source alludes to the tradition of creating light as an illusion within the body of a painting to suggest depth and direction.

In the central space of the gallery the dialogue of materials shifts away from painting, becoming more about the nature of sculpture. Michael Just’s Untitled Aluminum Models rest on open pedestals that incorporate real space into the works. Painted lines on curved metal forms convey a sense of minimalism and expressionism simultaneously. Barnett Newman’s zips and Jackson Pollock’s drips are alluded to in abstract expressionist marks applied to forms suggestive of parking cones and construction zones. Despite their geometric forms, the pieces act like masterpieces in the figural tradition of Donatello and Rodin, as subtle repetitions in colors and forms are evident only when the viewer circles the sculptures. While the painted marks and sculptural forms are unified in these pieces, somehow those elements nonetheless can be appreciated separately.

Also central to the gallery are pieces made from resins and plastics (materials that transformed the nature of both painting and sculpture—resulting in more flexible paint; and lighter, more organic sculptures). Christian Tedeschi’s Still speaks to the act of taking a picture with complete absorption as well as the resulting photographic image that stops time. Ironically the viewer has to look for a long time (much longer than the time it takes for the shutter to close) to see past Tedeschi’s resin stalactites and stalagmites to find an amber-imprisoned fossil. While Still is a closed sculpture, Untitled is dramatically open. A hand-made plastic model of a church has been heated and stretched by hand; the result is a trick of the eye as the material (cheap plastic) takes on the appearance of blown glass. Only close inspection reveals a tiny cross intact atop what is left of the steeple. Both of Tedeschi’s works suggest that commonplace activities can be made remarkable and perhaps dangerous.

Danielle Riede’s Love You Me spans the gallery’s windows. While it may be the first thing seen (certainly from outside) it is appropriate to consider it here last, because a portion of Riede’s found materials once belonged to other artists (desiderata, including blobs of paint shed from others’ canvases). The result is not a quote of someone else’s style, rather a physical appropriation of their materials. Riede’s process combines the collecting spirit of Kurt Schwitters with the arranging action of Judy Pfaff. Resin pieces cast from collected objects transform and multiply the readymades. Riede’s adopted orphans traverse delicate tightropes across the windows; the light transforms their appearance by heightening their colors and textures. Viewers will find conversations among the strands, as the abstract forms suddenly take on the appearance of animals or recognizable objects. Riede’s materials are relics connected to specific locations and memories of time; when activated during installation in the gallery, the concerns become more formal than narrative.

Perceptive viewers will detect important conversations occurring between the individual pieces displayed in Material Presence. Riede’s materials juxtaposed with Tedeschi’s contrasts incredible freedom with pendulous imprisonment. The stopped motion and inward pull of Tedeschi’s Still contrasts dramatically with the positioning of space at the middle of White’s Sports Moment. The strong vertical movement of McSpadden’s works plays against both the curves in Sall’s work and the expressionistic marks on Michael Just’s sculptures. Meanwhile the apparent lightness and industrial feel of Just’s works contrasts Grow’s organic heavy matter. The artists in this exhibition have, in a sense, collaborated with their materials to create balancing acts, collections, transformations and slight-of-hand; the resulting works exude personality that is greater than the sum of matter plus process.

Elizabeth Mix

Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art

Butler University